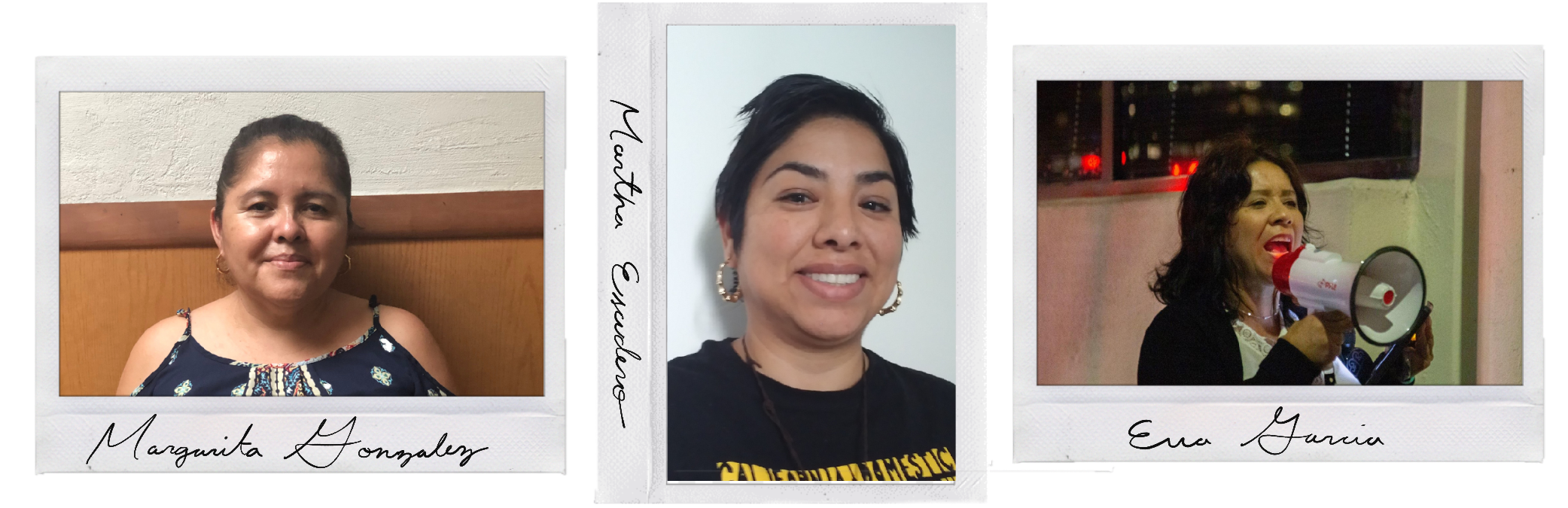

As part of the Sounds of California program, ACTA commissioned three community members of Boyle Heights, who have strong connections to community work in their neighborhoods, to document the expressive sights, sounds and stories that they felt reflected the heart and sense of belonging of their neighborhood: Martha Escudero, a housing activist who began occupying one of the 13 vacant CalTrans-owned homes in El Sereno with her two daughters as part of the “Reclaiming our Homes” movement that seeks to address the inequities stacked against unhoused and housing-insecure families during the pandemic; Margarita Gonzalez, a community member who runs a gelatina business with her son and co-leads an initiative that aims to secure dignified and affordable housing that is controlled by the residents of East LA alongside a collective of organizers known as the Fideicomiso de Tierra Libre community land trust; and Eva Garcia, an active leader in the same movement and other organizing spaces such as the Invest in Youth Coalition that puts pressure on the Los Angeles City Council to invest in a youth development department.

While familiarizing myself with the content these women collected, I noticed how they exist in multitudes—simultaneously taking on the roles of mothers, compañeras, community activists, organizers, health advocates, and now, documentarians. Although I’ve never met them in person, Eva, Martha, and Margarita radiated the kind of warmth that I could only recognize in my tías. In a way, as an archivist it was my job to live vicariously through their lives while assigning digital tags to the intimate snippets of sounds, images, and footage that made up the lifeblood of their work. There was an innate familiarity that I could sense in the footage they stood behind—a mutual sense of recognition existed in every conversation they had and the connection they made with their fellow neighbors.

EVA

Eva’s lens focused on the direct actions of anti-eviction protests, along with spotlighting the unsung labor of the women in Boyle Heights who organize and fight for the well being of their community:

I wanted to focus on how our community fights — to show many people that day after day they fight for something different, for justice, because there are many needs.”

— Eva Garcia

MARTHA

Martha often captured people coming together for vigils and rallies, and also offered a first person perspective into the Reclaiming our Homes movement with her daughters, Mezti Kali and Victoria:

There are justice seekers and community organizers–even though things are tough, they keep fighting, and that gives me a lot of admiration for the people in Boyle Heights.”

— Martha Escudero

MARGARITA

Margarita’s documentation offered insight into the familiar faces behind local businesses and the memoirs of Boyle Heights elders:

I want people to see that my community is made up of small businesses, street vendors, people who struggle. I want them to see the historical places, the culture that is reflected in art, how families live.”

— Margarita Gonzalez

Despite having to confront a devastating year marked by the violence of white supremacy, racial injustice and a global pandemic, these three women captured the community’s resilience and inclination to support one another in need. During this time, neighbors and friends showed up for one another through mutual aid initiatives, fundraisers, and food distributions. As COVID-19 continued to stifle the world, local business owners and restaurants fed and provided their communities with basic necessities to survive and helped heal one another in times of grief and unrest.

As Eva, Margarita and Martha documented the historic and pivotal moments that the many hardships of 2020 brought forth, they would find the beauty in some of the most overlooked details of the community, unearthing the stories that ran through the veins of their neighborhood: the chirping sounds of the birds and wildlife in the trees, the inviting noise of street vendors on every corner, the not-as-busy-any-more residential streets where children played in their front yards, the powerful drumming of danza ceremonies, the impassioned protestors marching towards Mariachi Plaza. They shaped this archive into something that prioritized the voices of working-class community leaders and culture bearers, contributing something that couldn’t be replicated by even the most seasoned professional journalist — something deeply tapped into the intimacy, trust, care, and authenticity that is embedded into the soul of their neighborhood.

In wrapping up my work on this project, I had the opportunity to ask Eva, Margarita, and Martha a few questions about their experiences as documentarians.

How would you describe the experience of taking on the role of a documentarian for your community?

Eva

It was something very beautiful for me…the truth is there is a lot of work in my community. I am very proud, because I have many friends who do a lot of work for their community and have never been recognized. I wanted to document so much more…I get emotional thinking about it. I love being in efforts that fight for our communities, it’s like pure adrenaline for me.

As community members of Boyle Heights, what did it mean for you to document all the work being done behind a camera?

Margarita

The truth is, I had never participated in work like this. My job is very different from this…I remember saying “what did I get myself into?” because I couldn’t even send a text message…I didn’t know how I was going to talk to people. I don’t have a problem with talking, but being with a person directly and asking them questions? If I stutter while talking with my family, I couldn’t imagine how it would go with other people. But it ended up being something wonderful because I got to know people more.

I have been here for almost 30 years, and doing this made me reflect on my life here from the moment I arrived, all the changes that have arisen within the community. I never thought that I would be living here in a place that has such a history.

Because here where I live [in Mariachi Plaza]…it’s a place where many gather to protest, to spend happy moments, to get to know my neighbors more. I learned much more from my community, and much more from my peers.

Martha

It was interesting learning about my own history in Boyle Heights. My family has been here since my grandparents, but I hadn’t explored it’s history among the businesses that are still present. My mother’s first job was at Cinco Puntos in the 1970s, I was born in the General Hospital where I used to work, and I had my second daughter at home in Boyle Heights. All of this reminded me of my own story. Also among the music of Boyle Heights, a lot is known about Mariachi, but there is a lot of diversity in the music and in the people who live here…it was interesting to learn that there really is a lot of diversity. There are justice seekers and community organizers—even though things are tough, they keep fighting, and that gives me a lot of admiration for the people in Boyle Heights.

Eva

At the beginning, I said, how am I going to do the interview? What am I going to ask them? I get confused a lot…although I talk a lot, I didn’t know how to do it. At first I was a little nervous. It was something different, but I learned how to use technology a little more. I really admire people who do journalism and confront all the things that are challenging. I am a cook, I’ve always dedicated myself more to cooking and organizing.

Being a part of this project changed the perception that I have of myself. It was something extraordinary for me.

What kinds of stories were you interested in telling personally?

Eva

My community is a source of pride, it is a community that is always fighting for a better life, for the people who are the most vulnerable…I know that there are many comrades who are here fighting for change. There are many comrades who make this fight day by day, who are facing different actions; I think I wanted to highlight a lot of that. I wanted to focus on how our community fights—to show many people that day after day they fight for something different, for justice, because there are many needs.

Margarita

What I want people to see in my community is that it is made up of small businesses, street vendors, people who struggle. I want them to see the historical places, the culture that is reflected in art, how families live, and what they think of the community where they live; from adults to children, the stories told by their own words. That is what is lived in the community—is its people, and that’s what I wanted to be reflected.

Martha

At first I wanted to interview more people, but now with the pandemic it was a challenge for going through with many of the interviews I had planned. My vision was also to tell the story that many people who are not from Boyle Heights do not know, how the small businesses that have been there for decades. I also wanted to focus on diversity; that the people who live here are not only Mexican, but culturally they have always been very diverse. There is a mixture of so many foods and cultures…there are a lot of Mexican community members, but there are still Japanese families living there and there are also Black families.

Our music is not just mariachi; there’s banda, there’s son jarocho, there’s hip-hop, there’s cumbia. There is diverse music here that is part of our culture.

Holding on to hope during a pandemic is difficult when the government has consistently failed in addressing the instability of health-care, housing, and food security for working-class, low-income communities that have been hit the hardest by the virus. Today, gentrification, rising rates of unemployment, and tenant evictions continue to impact the families and cultural communities of Boyle Heights. Today, we still see tepid responses towards providing sustainable relief and policies that are driven by the preservation of profit over the protection of the people. But Eva, Martha and Margarita show us how the roots of this locality in East Los Angeles are deeply embedded into the soil and grounded by community. The resilience of their neighbors gestures towards signs of a new leaf sprouting through the debris of a crumbling city—where a hopeful tomorrow exists.

Being a visitor to Boyle Heights, I approached the role I had in this project with a readiness to learn and willingness to understand the essence behind the sights and sounds these women captured through the camera. But the story they tell of their neighborhood is simple:

The children will continue to imagine. The elders will continue to teach. The artists will continue to envision. The musicians will continue to play. The protestors will continue to march. The original stewards of the land will continue to protect. The local businesses and street vendors will continue to feed the neighborhood. The community will continue to defend, reclaim and rebuild itself.

If you listen closely to the sounds of Boyle Heights, you can hear its heartbeat.

Nestor Guerrero is an aspiring multimedia storyteller from Whittier, CA and a recent graduate from UCLA, where he studied Chicana/o/x + Central American Studies and American Culture, with a minor in Digital Humanities. He is currently a DJ and programming assistant at the Boyle Heights Arts Conservatory community radio station (KQBH-LP 101.5 FM) where he hosts his own show “Public Memoir.”

Nestor Guerrero is an aspiring multimedia storyteller from Whittier, CA and a recent graduate from UCLA, where he studied Chicana/o/x + Central American Studies and American Culture, with a minor in Digital Humanities. He is currently a DJ and programming assistant at the Boyle Heights Arts Conservatory community radio station (KQBH-LP 101.5 FM) where he hosts his own show “Public Memoir.”

Nestor Guerrero

Nestor Guerrero

ACTA Media and Archives Intern Nestor Guerrero takes us inside ACTA’s

ACTA Media and Archives Intern Nestor Guerrero takes us inside ACTA’s