If there is one driving message of the late Danongan ‘Danny’ Kalanduyan, who is credited for introducing kulintang music (literally meaning golden sound moving) to the US, it was that he wanted his own people to understand their music. “Three hundred and fifty years of Spanish colonization influenced so much of the Philippines that this ancient music practiced by the tribes in the south is not recognizable to them.” This quote can be found on the National Endowment of the Arts website where Danny is a featured 1995 National Heritage Fellow. This being our nation’s highest honor for a traditional artist and culture-bearer, the quote encapsulates his tireless teaching and performing career in relation to his community. Another example of Kalunduyan’s artistic leadership in his many community-based projects can be seen in his 2001 Creative Work Fund collaboration with the Ethnic Studies Department at San Francisco State University. A two-year collaboration among Kalanduyan, as the lead artist, professor Dan Begonia of the Ethnic Studies Depart at SF State, and the Ating Tao Drum Circle, a Pilipino American student performing group, led to performances of new works based on traditional kulintang music and dance from the Southern Philippines. In 2009, Danny was awarded a Broad Fellowship in Music with the United States Artists, which recognizes the most accomplished and innovative artists in the US, emphasizing the importance of originality across every creative discipline.

Danongan Kalanduyan was born and raised near the fishing village of Datu Piang, Maguindanao province, on Mindanao Island in the Southern Philippines. Learning to play the instruments of the kulintang came initially from watching his mother play. He often recalled that transmission was a natural byproduct of being surrounded by this music. Not only was kulintang a part of daily life—its percussive gongs and drum punctuated all life cycle events. It is not an exaggeration to say that most traditional kulintang music that is performed in North America is a reflection of Danny Kalanduyan’s musical style and his family’s kulintang compositions.

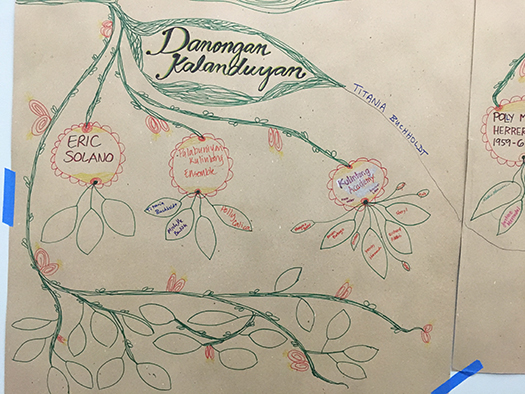

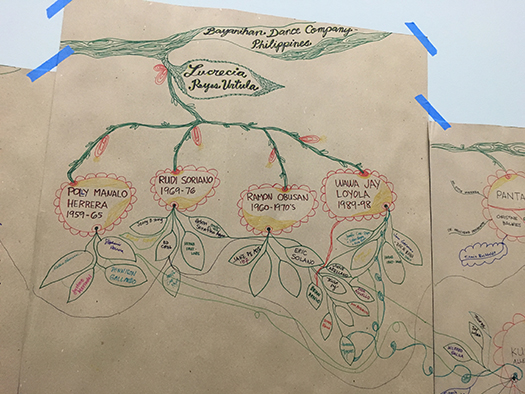

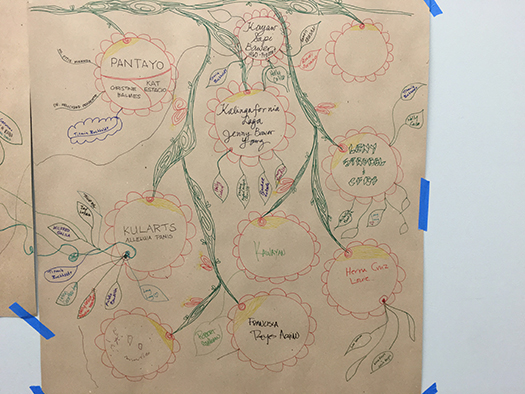

Local Genealogy: From the Tree Grows the Branches

I am not sure if Danny ever saw this butcher paper genealogy of Pilipino arts and culture of the Bay Area. On this representation of a hand-drawn tree are branches, flowers, and fruits that trace the offshoots of Danny’s influence. His name sits at the very top, crowning the growth of a large tree and below are names of significant individual artists, community leaders and activists. They reflect the many excellent Pilipino dance companies, theater groups, hip-hop and spoken word collectives, as well significant new directions towards the reclamation of indigenous healing, tribal weaving and Babayin language studies.

The occasion for this visualized depiction of Pilipino American art-making was a two day gathering in May 2016, co-presented by the University of San Francisco’s Performing Arts and Social Justice Department and KulArts, a stalwart San Francisco non-profit which produces both contemporary and indigenous Pilipino performance. Entitled, “Dialogue on Philippine Dance + Culture in the Diaspora”, I was there on behalf of ACTA to talk about the larger field and potential support opportunities. Before speaking to the group, I gave pause to absorb the self-documentation of the community, who through this artistic family genealogy, acknowledge that traditional practices fully animate all aspects of these artistic pursuits. In fact, from our ACTA vantage point, we recognize that there is a renaissance of art-making in the Pilipino-American community and it can be seen throughout the state. It is characterized by a self-assurance that was less evident even two decades ago. Many dance companies include repertoire of the Muslim North, where once the dance menu was dominated by the Philippines national folkloric dictates that favored the Spanish dominated culture, and Pilipino tribal groups like the Kalinga of San Diego are exposing their youth through their gatherings to the community culture-bearers. More exchanges take place between California and the Philippines than ever before in pursuit of respectful representation and cultural immersion. Themes of indigeneity play a large part in projects that support the learning of traditional medicine, back-strap weaving, and even Tagalog immersion summer programs for youth that seeks to lift up the pre-colonial roots of Pilipino identity as exemplified by the Sama Sama Cooperative in Berkeley (http://actaonline.org/content/sama-sama-cooperative).

If the drawing of the tree is any measure of influence, Danny’s life work has been a catalyst and has served as an anchor for so many of these pursuits. Again, citing from the NEA page, “… Word of his presence spread among Pilipino communities, and he was soon very much in demand as a performer and a teacher. He has taught and performed with virtually all the American kulintang ensembles. It is ironic to some that kulintang music, almost entirely confined to a small Muslim minority in the Philippines, has been enthusiastically embraced by scores of young Christian Pilipino-Americans for whom, through its pre-Hispanic, pre-Muslim roots, it now serves as a cultural icon of pan-Pilipino-American unity.”

***

We here at ACTA will miss Danongan Kalanduyan. ACTA’s long relationship with Danny supported the transmission of his knowledge to several apprentices. In 1998, Danongan was a master artist in the inaugural round of our Apprenticeship Program, with apprentice Titania Buchholdt, and again in 2007 and 2013, with his long-time apprentice Conrad Benedicto. The Mindanao Lilang Lilang/Palabuniyan Kulingtang Ensemble received numerous grants from ACTA’s Living Cultures Grants Program over the years, including an award in 2010, that supported the purchase of instruments to be housed at the Pilipino Community Center and Balboa High School, where Kalanduyan and members of the Ensemble taught classes for several years. and a Living Cultures grant in 2008, where , free classes were provided for the community with Danny traveling to neighborhoods that were largely Pilipino. He was always generous with his time, gracing our artist convenings with his presence, tirelessly demonstrating the kulintang to groups, both large and intimate. In this last period of his life, the demand for his expertise did not dim. In fact, he continued to plant new seeds, establishing an ensemble in Stockton, which has a significant place in Pilipino-American history because it was where immigrant farmworkers first protested unfair working conditions, giving rise to the movement we have come to associate with Cesar Chavez.

Our last encounter with Danny and the Palabuniyan Kulintang Ensemble occurred on December 6, 2015 for our inaugural Sounds of California concert at the Oakland Museum of California, where through the lens of immigration and migration, we explored the themes of our State’s diverse population. This was our final concert and conversation with Danny whose contributions to our California traditional arts community has been tremendous. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7doqhTB_Dk8

More on Danongan Kalanduyan:

A celebration of his life and public memorial will be held in San Francisco on November 5-6, 2016:

http://kularts.org/wp/be-a-part-of-danny-kalanduyans-memorial-nov-5-6/

A fund to assist the family with funeral costs has been started by his students. Danny Kalanduyan Memorial Fund https://www.gofundme.com/dannykalanduyan.

The Cotabato Sessions: A Film and Music Album. This film, created in 2013 by Producer Susie Ibarra and Director Joel Quizon, followed Danny home to the Philippines. This beautiful portrait is an intimate look into the context and family of his music. It is released in honor of Danny’s memory. https://vimeo.com/97298820.